About the song

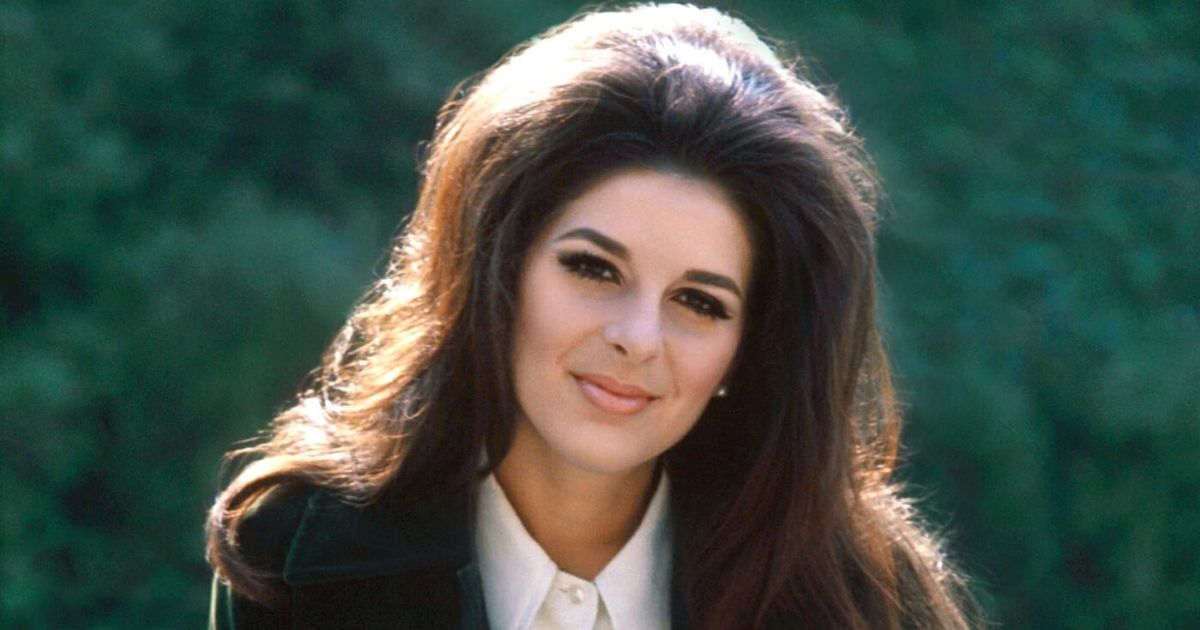

Released in 1967, “Ode to Billie Joe” by Bobbie Gentry stands as one of the most enigmatic and influential songs in American popular music. Blending elements of Southern Gothic storytelling, folk, and country-soul, the song captivated listeners with its haunting narrative and atmospheric restraint. Gentry’s smoky voice, paired with sparse acoustic guitar and string accompaniment, creates an intimate yet unsettling portrait of small-town life in the Mississippi Delta — a world where tragedy unfolds quietly under the surface of ordinary conversation.

The song was Gentry’s debut single, written, composed, and first performed by her. Upon release, it became an unexpected phenomenon, reaching #1 on the Billboard Hot 100, selling over three million copies, and earning Grammy Awards for Best New Artist and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance in 1968. Beyond its commercial success, “Ode to Billie Joe” is remembered for its narrative ambiguity, subtle social commentary, and Gentry’s groundbreaking authorship as one of the first major female singer-songwriters to achieve full creative control over her material in the male-dominated music industry of the 1960s.

Narrative and Themes

At its core, “Ode to Billie Joe” tells the story of a family sitting down to dinner on a summer afternoon, discussing — in a remarkably detached manner — the shocking news that a young man named Billie Joe McAllister has jumped to his death from the Tallahatchie Bridge. The narrator, a young woman, listens silently as her parents and brother casually exchange information and gossip, unaware (or perhaps willfully ignoring) that she herself shared a personal, possibly romantic, connection with Billie Joe.

The song’s power lies not in what is said, but in what is left unsaid. The family’s dinner conversation is chillingly mundane — they discuss chores, harvest, and social visits — juxtaposed with the revelation of a suicide. This contrast between emotional indifference and human tragedy exposes the quiet repression and moral conservatism of Southern rural life. It reflects a world where pain and scandal are buried beneath politeness and denial, and where empathy is often silenced by social norms.

The central mystery — why Billie Joe jumped off the bridge, and what the narrator and Billie Joe were seen throwing off the bridge days earlier — has fueled decades of speculation. Gentry herself deliberately left these details unresolved, explaining in interviews that the song was not about the mystery itself, but about how people respond to tragedy. The object tossed into the river and the suicide are narrative devices, she said, meant to reveal the emotional distance and casual cruelty of human behavior.

Musical Style and Atmosphere

Musically, “Ode to Billie Joe” is deceptively simple. The song opens with Gentry’s fingerpicked acoustic guitar, establishing a slow, hypnotic rhythm that mirrors the languid pace of life in the Delta. Her voice — sultry, conversational, and understated — draws the listener into the scene like a whispered confession.

The arrangement is sparse but effective. Producer Jimmie Haskell added a subtle string section that enters midway through the song, heightening the sense of unease and melancholy. Rather than overwhelming the vocals, the orchestration deepens the atmosphere, evoking the stillness and heat of a Southern afternoon. The result is a hauntingly cinematic experience, one that feels both intimate and timeless.

Social and Cultural Context

“Ode to Billie Joe” arrived at a time when American popular music was shifting toward more personal and narrative-driven songwriting. Alongside contemporaries like Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, Gentry helped redefine the role of the singer-songwriter. But unlike many of her peers, she rooted her storytelling in Southern Gothic tradition — a style influenced by writers such as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Eudora Welty.

The song paints a vivid picture of Southern life marked by poverty, gossip, religion, and emotional restraint. Gentry’s lyrics capture the rhythm of rural speech — the mother’s casual tone, the brother’s matter-of-fact remark — creating a chillingly authentic sense of place. Beneath the surface, however, the song subtly challenges the listener to question the moral fabric of that world. Why is tragedy treated so casually? Why is the young woman’s grief ignored? In this way, Gentry’s song becomes both a social critique and a psychological study of repression and isolation.

Moreover, as a female songwriter in 1967, Gentry broke new ground. She wrote, arranged, and performed her own material, a rarity at the time. Her portrayal of a young woman navigating emotional trauma without explicit expression of her pain mirrored broader social themes of female silence and invisibility — issues that would become central to feminist discourse in the following decade.

Legacy and Interpretation

Over the decades, “Ode to Billie Joe” has inspired countless interpretations, cover versions, and even a feature film adaptation (1976) that attempted to “solve” its mystery — though Gentry herself rejected the film’s literal approach. The song’s endurance lies in its ambiguity, which allows each generation to project new meanings onto it.

It remains a masterclass in economical storytelling — a four-minute song that conjures a whole world, rich with texture, emotion, and unanswered questions. Its blend of folk minimalism and narrative sophistication continues to influence artists across genres, from country and Americana to pop and indie folk.

Conclusion

“Ode to Billie Joe” is more than a song; it is a literary short story set to music, a portrait of a time, place, and emotional landscape that feels hauntingly real. Through her restrained storytelling, Bobbie Gentry captures the tension between surface normality and hidden suffering, between what is spoken and what remains unsaid. In doing so, she crafted one of the most unforgettable works in American music — a song that continues to intrigue, unsettle, and move listeners nearly six decades later.